Abstract

This study investigates the safety risks associated with water hammer in the operation of long-distance, negative head water pipelines. Using the Jinzhou Supporting Water Supply Project as a case study, a mathematical model was developed to evaluate various water hammer protection measures and analyze effective countermeasures. The findings suggest that integrating an air valve with a pressure-regulating chamber provides superior water hammer protection, offering low project costs and facilitating construction and maintenance. This combined approach is recommended for implementation in engineering design and construction projects.

Long-distance water transmission projects are critical engineering solutions designed to address spatial and temporal disparities in water resource distribution, thereby enhancing utilization efficiency. Consequently, governments at various levels allocate substantial funds, manpower, and materials to the construction of these projects. Pressurized water pipes, particularly negative head systems where the upstream water level exceeds the downstream level, are the predominant method for long-distance water transmission. These systems offer advantages such as cost-effectiveness, safety, and efficiency, making them the preferred choice in water pipeline construction. However, in scenarios where the elevation difference between upstream and downstream is minimal, terrain factors necessitate additional pressurization at pump stations to meet water supply requirements.

Under normal operating conditions, long-distance water supply pipelines typically function without issues. However, emergencies such as power failures, pump station shutdowns, or improper valve operations can induce water hammer, jeopardizing pipeline integrity. Current research on water hammer protection in long-distance water diversion projects primarily focuses on selecting protective facilities and implementing hydraulic control measures. Notably, studies addressing hydraulic control in long-distance negative head water supply projects remain limited. Given the complex hydraulic transitions and elevated risks of water hammer in these systems, dedicated research is essential to develop tailored protection strategies. Such studies are crucial for ensuring the safety, reliability, and efficiency of long-distance negative head pressurized water supply systems.

1. Project Background

The Jinzhou City Supporting Water Supply Project is a crucial initiative designed to address the disparity between water supply and demand in Jinzhou City, curb excessive groundwater extraction, and alleviate the severe water scarcity in northwest Liaoning. This project involves the construction of a pipeline and pump station extending from the water treatment plant to the Xingshan Integrated Pump Station. The pipeline stretches 23.1 kilometers and is constructed using Prestressed Concrete Cylinder Pipe (PCCP) with a diameter of 1.40 meters. The water inlet elevation at the pressurized section is 160.30 meters, while the outlet elevation at the terminal is 156.40 meters. Under low-flow conditions, gravity facilitates water conveyance. However, during high-flow scenarios, pumps are activated to maintain adequate pressure. The pump station operates three identical pumps in parallel, each designed for a flow rate of 30 m³/s, a head of 58.50 meters, and a rated speed of 375 rpm.

2. Calculation Method

2.1 Fundamental Equations of Water Hammer

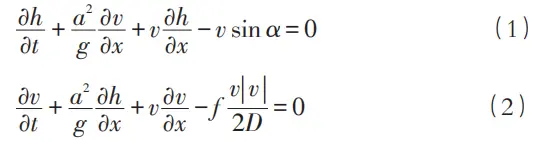

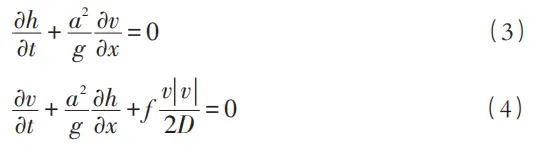

The primary equations governing unsteady flow in pressurized pipes are the continuity equation and the momentum equation:

Where: h represents the pressure head (m); t denotes time (s); a signifies the water hammer wave velocity (m/s); g stands for the acceleration due to gravity (9.80665 m/s²); v indicates the flow velocity within the pipe (m/s); x is the spatial coordinate along the pipe; α denotes the pipe's inclination angle (degrees); f is the Darcy-Weisbach friction factor; and D represents the pipe diameter (m). Typically, the flow velocity within the pipe is considerably lower than the water hammer wave speed. Therefore, the convective acceleration term in the fundamental equations is frequently neglected in calculations. Moreover, owing to the negligible elevation difference between the pipeline's upstream and downstream sections in this study, the inclination term can be disregarded. Consequently, the following simplified equations are employed in this study's calculations:

2.2 Calculation Method

Advancements in numerical simulation techniques for hydraulic transient flow have significantly enhanced the modeling of transient phenomena in water supply systems. These methods are extensively employed worldwide to analyze water hammer effects and develop mitigation strategies in long-distance water conveyance pipelines. Commonly utilized hydraulic transient flow calculation techniques encompass the method of characteristics, finite difference method, finite element method, and finite volume method. Among these, the method of characteristics is preferred for water hammer simulations owing to its computational precision, numerical stability, and straightforward implementation, including efficient handling of boundary conditions. Consequently, this study adopts the method of characteristics to model the water hammer pertinent to the project. The computational approach follows the procedural framework outlined by Wylie et al., which involves converting the pipeline's continuity and momentum equations into a system of ordinary differential equations. These equations are subsequently integrated along characteristic lines to derive finite difference equations, facilitating efficient programming and computation. Ultimately, the derived differential equations are solved numerically on a discrete computational grid through algorithmic implementation.

The computational model's boundary conditions primarily include the upstream reservoir, valve, and air valve. Water level fluctuations in the upstream reservoir are minimal, having a negligible effect on water hammer pressure; therefore, a constant water level is assumed in the analysis. The valve is modeled using the steady-state orifice equation, which simplifies flow characteristics by neglecting inertial effects from fluid acceleration or deceleration and assuming a constant fluid volume within the valve. It is also assumed that pressure within the air tank's air chamber remains uniform at all times, and that the gas thermodynamic process follows a reversible polynomial relationship. Additionally, the gases in both the air valve and the pressure-regulating chamber are considered ideal, capable of isentropic flow, with minimal influence on the pipeline's water height. The water pump is represented using the unit rotation equation and the head balance equation.

3. Calculation Results and Analysis

3.1 Accidental Pump Shutdown Scenario

The simulation models an accidental pump shutdown in the project. Post-shutdown, the pump remains stationary without reversing.The maximum positive pressure recorded in the pipeline is 66.88 meters of water head at station 7+069.14, aligning with the pipeline's design pressure limits. As the pressure wave moves downstream, negative pressures emerge, with most sections reaching levels conducive to cavitation. The most severe negative pressure is -39.78 meters of water head at station 21+062.33, which could lead to water column separation and subsequent water hammer damage. Implementing appropriate protective measures is crucial to ensure the safety of the water diversion project.

3.2 Air Vessel Protection

An air vessel is installed downstream of the pump to promptly supply water to the pipeline after an accidental shutdown, thereby preventing negative pressures and mitigating water column separation. Simulations and optimizations suggest that an air vessel measuring 28.00 meters in height and 22.00 meters in diameter at the pump outlet offers optimal engineering and economic benefits. The calculations show that the maximum reverse speed of the pump after shutdown is 410 rpm, approximately 1.08 times its rated speed, meeting engineering design requirements. The peak positive and negative pressures in the pipeline are 56.99 meters and -1.21 meters, respectively, occurring at stations 7+069.14 and 20+053.41. These results indicate that installing an air vessel downstream of the pump effectively protects against both positive and negative pressure surges in the pipeline. However, the calculations also reveal that the air vessel experiences leakage after the pump stops, failing to meet relevant specifications. Therefore, adopting this solution would require increasing the vessel's volume, which could negatively impact the project's economic feasibility.

3.3 Air Valve Protection

Air valves are installed at elevated points along the pipeline to introduce external air during pump shutdowns, thereby preventing vacuum formation and mitigating water column separation. Through comprehensive calculations and simulations, 15 strategic locations were identified for the installation of 150 mm diameter combination air valves. The results indicate that, with air valves alone, the pump does not undergo reverse flow. However, the pipeline's maximum and minimum pressures are 56.99 meters of water head (at station 7+069.14) and -6.83 meters of water head (at station 21+003.85), respectively, which do not satisfy the engineering design's minimum pressure requirement of -2.0 meters. While air valves improve the pipeline's resistance to negative pressures and offer some protection against water hammer, their effectiveness is limited due to significant pressure fluctuations observed along the pipeline. Therefore, further optimization of water hammer protection measures is necessary.

3.4 Combined Air Valve and Pressure Regulating Chamber Solution

The air valve pressure regulating chamber integrates the functionalities of both air valves and air tanks. Its purpose is to introduce air into the pipeline during pump shutdowns, thereby preventing negative pressure and mitigating water hammer effects. Based on prior calculations and the specific requirements of the project, the air valve system was optimized. In regions experiencing significant negative pressure, six air valves were replaced with air valve pressure regulating chambers, each measuring 2.00 meters in diameter and 5.00 meters in length. A combination air valve with a diameter of 150 mm is installed at the top of each chamber. The specific locations of these chambers are detailed in Table 1. Additionally, the diameter of the remaining nine air valves was reduced to 100 mm.

Table 1 Air valve pressure regulating chamber position parameters

|

Pile Number |

Bottom Elevation (m) |

|

3+480.20 |

154.38 |

|

6+234.00 |

153.67 |

|

10+875.50 |

152.89 |

|

16+223.00 |

152.48 |

|

17+002.10 |

151.34 |

|

20+051.10 |

150.11 |

The proposed solution underwent simulation and analysis, revealing that the water pump did not experience reverse flow. The maximum pipeline pressure recorded was 56.99 meters of water head at station 7+069.14, while the minimum pressure was -0.21 meters of water head at station 22+331.56. By implementing an air valve pressure regulating chamber at a strategically selected location within the pipeline, negative pressure was effectively mitigated, improving the minimum pressure from -6.83 meters of water head to -0.21 meters of water head. This approach facilitates straightforward construction and maintenance, offering notable engineering benefits. Compared to the air tank alternative, it provides superior economic and protective advantages.

4. Conclusion

This study addresses the challenge of controlling water hammer in long-distance, negative head, pressurized water pipelines. A mathematical model was developed to evaluate various protection strategies, leading to the identification of the most effective design solution. This methodology offers valuable insights for both the current project and similar future endeavors aimed at preventing water hammer. The air valve pressure regulating chamber employed in this study has a fixed size; however, future research could optimize its dimensions based on the negative pressure characteristics of different pipeline sections to enhance protection. Furthermore, considering the diverse geological conditions and design specifications across pipeline projects, customized analyses should be performed to tailor water hammer mitigation strategies to the specific engineering requirements of each project.